Familiar Physical Laws

The Everyday Macroscopic World

The Gas Laws

As we continue to reduce our vision from global to local, we might consider as an example the forces that control the weather. Gravity drives convection cells in the atmosphere and their full description utilizes a number of specialized topics as indicated in the inset diagram. We might scale “free convection” by the so-called Rayleigh’s number (named after a 19-century British physicist) that scales convection forces of hot air rising against gravity and is relevant to everything from

smoke going up a chimney to global weather patterns. The principal relationships we could use in this example are from several branches of sciences: thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, and energy conservation principles, among them. We will get the most traction in our present context by considering the simplest of the “laws” that describe the conditions of a gas. These laws are based on experimental observations that are ~ 340 years old.

As we continue to reduce our vision from global to local, we might consider as an example the forces that control the weather. Gravity drives convection cells in the atmosphere and their full description utilizes a number of specialized topics as indicated in the inset diagram. We might scale “free convection” by the so-called Rayleigh’s number (named after a 19-century British physicist) that scales convection forces of hot air rising against gravity and is relevant to everything from

smoke going up a chimney to global weather patterns. The principal relationships we could use in this example are from several branches of sciences: thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, and energy conservation principles, among them. We will get the most traction in our present context by considering the simplest of the “laws” that describe the conditions of a gas. These laws are based on experimental observations that are ~ 340 years old.

To get to the Gas Laws let’s start with some natural units for thermodynamics and energy principles. The most important of these is the concept of the mole; the gram mole is also known as a “mole” and its units are “mols”. One mole of anything (H2 molecules, H atoms, CO2 molecules, Ar atoms, U atoms, electrons, H2O molecules, Ne plasma ions, etc.) is defined as 6.023 × 1023 particles. This is known as Avogadro’s number, symbol NAv. It doesn’t matter what the phase is; so H2O can be ice, water or steam, and still one mole or 18.0 grams of H2O “stuff” contains 6.023 × 1023 molecules.

Many real gases behave somewhat like a conceptual “Ideal Gas” and therefore occupy the same volume under the same conditions: at 1 atmosphere pressure and 0°C (“NTP” standing for normal temperature and pressure). Thus two grams of hydrogen gas molecules or 1 gram of hydrogen gas atoms would each occupy 22.4 liters of volume (assuming you could stabilize hydrogen atoms from reforming hydrogen molecules at that temperature[1]). The same thing is true for 44 grams of carbon dioxide gas, 40 grams of argon gas, 550 micrograms of an electron gas and 20.2 grams of neon ions in a discharge tube – all provided they are in the gas phase at NTP (and with extensions for pressure and temperature corrections if not at NTP).

We can also use the kg mole (“kmol” is acceptable as its unit) or 6.023 x 1026 particles, the only difference being between that an Avogadro’s number defined above is that it’s the number of particles in one kg mole, not one gram mole. Its associated molecular volume is also 1000 times larger than that for a mol so 1 kg. mole of an Ideal Gas occupies 22.4 m3 of volume.

For every gas approximating “ideality”, the combination of Boyles’ and Charles’ Law gives the “Ideal Gas Law”.

In these equations, p is the pressure any (ideal) gas would exhibit if it occupied a volume

V at an absolute temperature T (in kelvins, or K - there is no ° sign for this unit). If we need

![]() again, the tilde will remind us we are dealing with moles, not masses. For gases in mol units the value of

again, the tilde will remind us we are dealing with moles, not masses. For gases in mol units the value of

![]() is 8.314 J/mol K and is a factor of 1000 less than if

is 8.314 J/mol K and is a factor of 1000 less than if

![]() is based on a kg moles,

i.e., 8,314 J/kmol K.

is based on a kg moles,

i.e., 8,314 J/kmol K.

We are much better off with the universal form of the ideal gas laws since it shows all ideal gases at the same temperature and pressure have the same number of moles (hence, the same number of molecules or atoms as the case may be) occupy the same volume. The Ideal Gas Law can be written in terms of “n”, the number of molecules per unit volume. This number is obtained from the number of moles in volume V, N/V:

By substituting back into the Ideal Gas law for N moles, we see that:

Evidently the universal gas constant divided by Avogadro’s number is a ratio of constants and is itself another constant that is called the Boltzmann constant, k, and has a numerical value of 1.3807 × 10-23 J/particle K. Substituting this constant back into the Ideal Gas Law gives another useful form that is applied to one particle rather than to an assemblage of many, i.e.,

![]()

At NTP, every cubic centimeter of ideal gas contains the “Loschmidt” number, n = 2.7 × 1019 particles/cm3. Hence every cubic centimeter of gas around you has a staggering ~ 3 followed by nineteen zeroes of molecules of air (actually a mixture of mostly 21% O2 and 79% N2) in it! Multiply by 106 for particles/m3.

The Kinetic Theory of Gases

As scales contract we enter the world of atoms and electrons. One simple way to initially think about it is to use the Boltzmann form of the Ideal Gas Law. It is derivable, not only from experiments (as by Charles and Boyle), but also from a physical model that looks at the individual particles that form the ideal gas. In this model, they are point-size, very hard, billiard or pool balls distinguished only in their random speeds and directions. They collide with each other more often than with the container for the gas. The phenomenon of pressure is a result of momentum-transferring collisions with the container walls. The gas particles hit the wall and bounce back and hence, by Newton’s 2nd Law of Motion, there is a net force on the wall and thus, dividing by the area of the wall, a net pressure of the gas on the container’s walls. The results of this analysis are powerful while simple:

![]()

in which the term mn is the total mass of the molecules/volume that are contained within the box.

The mass of an individual particle is m (typically ~ 10-23 grams), and the mean speed of these particles is

ū (typically ~500 m/s at 300 K). Then ![]() is merely the average kinetic energy of the molecules/per unit volume that hit the wall. Thus, we have an interesting conclusion: the kinetic energy of translating gas particles is,

is merely the average kinetic energy of the molecules/per unit volume that hit the wall. Thus, we have an interesting conclusion: the kinetic energy of translating gas particles is,

![]()

a result reminiscent of the ideal gas law expressed as ![]() . The expression for the K.E. of the gas molecules is best interpreted as ½

kT per orthogonal direction of the randomly translating 3 dimensional motions of the average particle in the box.

. The expression for the K.E. of the gas molecules is best interpreted as ½

kT per orthogonal direction of the randomly translating 3 dimensional motions of the average particle in the box.

So, the per particle kinetic energy depends only on absolute temperature, T. Knowing the mean particle K.E., we can also calculate the mean velocity of the gaseous particles. For example, with a little re-arranging, the expression for K.E. leads to the molecular speed[2]:

![]()

Actually there is a distribution of molecular speeds in a gas that was first derived by Maxwell in the late 19th Century and built upon by Boltzmann and known as the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. Maxwell realized that random collision among gas molecules would distribute their kinetic energy in random fashion but that their average behavior could be tracked. The mean molecular speed of gaseous molecules can be shown to be:

![]()

At room temperature, the mean velocity of a gas particle is about 480 m/s at 300K and 1330 m/s at 2,000°C.

Because this deals with a true mean speed, the last equation is generally more useful than the related molecular speed. Of particular interest is the rate of gaseous molecules that impinge on an arbitrary surface imagined in the gaseous space. The picture is of a gaseous flux of

Because this deals with a true mean speed, the last equation is generally more useful than the related molecular speed. Of particular interest is the rate of gaseous molecules that impinge on an arbitrary surface imagined in the gaseous space. The picture is of a gaseous flux of ![]() molecules hitting a surface as shown in the inset diagram. Averaging this flux over the imaginary impingement surface leads to what is essentially the Hertz-Knudsen equation (also called the “effusion rate”), which, for the number rate of impingement of molecule per unit area, is

molecules hitting a surface as shown in the inset diagram. Averaging this flux over the imaginary impingement surface leads to what is essentially the Hertz-Knudsen equation (also called the “effusion rate”), which, for the number rate of impingement of molecule per unit area, is

![]()

(the more usual mass[3] rate formula is just

m × m). This is a very useful result since it allows us to figure possible rates of impingement of molecules onto a real surface sitting on the gas. The expression can be simplified in terms of macroscopic variables by substituting for n and for

![]() and re-arranging:

and re-arranging:

![]()

In this form, one can easily calculate how many molecules/s are impinging on a surface; e.g., at NTP, the impingement rate for water vapor (M = 18.0 kg/kmol) is 3.76 × 1027 molecules/m2s. Even for a good vacuum system (meaning low attained pressure) say p = 10-6 Pa, the impingement rate is still a very large number, 3.76 × 1016 molecules/m2s.

We will need to further explore and refine the physical model that led to the connection between kinetic energy of molecules and their temperature. The idea of collisions leads to the concept of “mean free path”1, the average distance between collisions of gaseous particles. Obviously as the pressure of the gas increases, the number of gas-to-gas collisions increase and vice-versa as the pressure falls. The relationship is:

![]()

In this expression σ is an effective cross sectional diameter for the atom or molecule. It enters the problem by looking at how large a volume can be swept by a finite sized gas particle as it travels through the soup of the other gas particles.

There is one other gas law concept that we will find very useful - how many binary collisions are there between gas molecules. The rate of collisions in a gas is clearly dependent on the mean free path between molecules as well as the speed of the molecules. After considering these criteria, the final expression is:

![]()

in which

![]() .

.

We have now reached atomic (or at least molecular) dimensions: How large is σ for a typical gas molecule? (Caution: these models are crude physical approximations to real molecules so these numbers should not be used indiscriminately):

| Gas | “Hard-sphere” molecular diameters[4] (nm) |

| He | 0.22 |

| H2 | 0.27 |

| N2 | 0.38 |

| O2 | 0.36 |

| CO2 | 0.46 |

Some points: these diameters are in nanometers (i.e., 10-9 meters), the first time it has been convenient to introduce the term “nano” in our scaling laws – a sure sign we are getting close to the heartland of this subject! Second, notice that the lightest particles (hydrogen and helium atoms) are small and the size increases with increasing molecular complexity (from one atom to two to three atoms per molecule – just as you would expect).

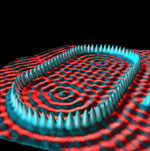

If we plug these numbers into our expression for mean free path, we can get some idea of the path followed by an average gas particle: for a 0.3 nm diameter gas molecule at atmospheric pressure, l ~ 100 nm at 0°C. To calibrate you: a good optical microscope can see ~ 0.5 micrometer particles or 500 nm. It’s also the approximately twice the size of many single cell organisms such as bacteria. A 100 nm spot is 10-7 meters diameter and we need an electron microscope to resolve that size. Finally the atom and molecular sizes of ~ 0.3 nm or smaller (as per the above table) can only be seen directly by the scanning tunneling or the atomic force microscope. You will definitely hear more about the STM and the AFM later in this course.

We can also calculate the collision rate, Z. The rate of binary collisions is also staggering; at NTP, Z = 1.6 × 1034 collisions/s/m3, but it comes down rapidly with pressure as proportional to p2. So at p = 10-6 Pa (a very good vacuum), Z = 1.6 × 1012 collisions/s/m3.

In the opposite direction as we get to high pressures, say 500 × atmospheric pressure, the gaseous mean free path calculates as l ~ 0.2 nm, or of the order of molecular size. The gas particles are basically filling the whole available volume and the assumptions of an Ideal Gas as point particles have long been violated. In fact we are looking more like a liquid than a gas in both molecular terms and in bulk terms (such as density, heat conductivity etc.). But the idea that atoms and molecules have motions will also be true in condensed matter (when we get there!).