Physical Laws

The physical laws that control everything we see are themselves universal (as far as we are aware). Yet how they act, and how we perceive them, depends very much on the scale over which these laws apply. For example, gravity is important to you and to me right now; it literally keeps us in our place. It acts as it does because of our relationship with the mass of the earth. Gravity is relatively weak and does its thing over large distances (over which distances other forces have long since effectively decayed to zero); gravity dominates the mechanics of large masses. On the other extreme, at the nuclear level, gravity is quite irrelevant but very short-range forces are predominant that affect, and effect, nuclear (and subnuclear) motions. In between these extremes of scale there are different forces at work.

The Laws of Nature appear quite different from each other. These forces act in evidently unrelated ways but what they cause to happen may be different faces of the same phenomenon. The grossest laws of which we are aware relate gravity and distance, speed, and mass via relativity. We observe many aspects of long distance forces at the everyday level, for example the motion of the moon around the

earth. But, as we know, at smaller scales, quantum mechanics rules electrons and atoms; at yet smaller scales, quantum mechanics and relativity interact to give us “quantum electrodynamics". At even smaller scales the laws are dictated by "quantum chromodynamics" and at the smallest scales presently conceived, “strings" may relate all of the above including gravity and quantum mechanics.

The Laws of Nature appear quite different from each other. These forces act in evidently unrelated ways but what they cause to happen may be different faces of the same phenomenon. The grossest laws of which we are aware relate gravity and distance, speed, and mass via relativity. We observe many aspects of long distance forces at the everyday level, for example the motion of the moon around the

earth. But, as we know, at smaller scales, quantum mechanics rules electrons and atoms; at yet smaller scales, quantum mechanics and relativity interact to give us “quantum electrodynamics". At even smaller scales the laws are dictated by "quantum chromodynamics" and at the smallest scales presently conceived, “strings" may relate all of the above including gravity and quantum mechanics.

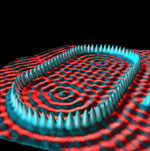

"Nanotechnology[1]", is the application of forces over a length scale of relatively large molecules so that these forces can influence how these molecules will move and orientate. This motion is called "self-assembly" and lies at the heart of nanotechnology. Self-assembly means that Nature is doing the hard work to construct the molecular grouping you desire. This may be in the context of organic compounds, inorganic structures, or living systems. In any case, the final product should have relied on molecular assembly to create the product rather than a series of anthropomorphically imposed synthetic steps. Unfortunately today there is no systematic approach to the study of the forces of self-assembly; each case is a special case; indeed in the vast majority of self-assembly processes it is not possible to quantitatively predict behavior.

The forces for self-assembly must operate at a scale commensurate with the reactive elements being assembled. At the smallest scale of interest in nanotechnology, these reactions are just classical chemical reactions in which forces are often short range and move only small molecular subassemblies such as chemical radicals. Of course, there is also a blurred line between ordinary chemical reactions and those to which the sobriquet “nanotechnology” should be applied. At the largest chemical reaction scales, relatively large molecules are bodily moved by forces acting over several molecular lengths as they are corralled into position. In chemistry, there are two relatively long-range sets of forces that are particularly important in moving relatively large molecular masses: hydrogen bonding and van der Waals bonding.

Some problems are open to “classical” modeling (meaning using relatively familiar macroscopic laws), while other microscopic systems involve quantum and statistical mechanical approaches[2]. In nanotechnology both macroscopic and microscopic regimes may be in play simultaneously and thus further complicating an already difficult subject.

As we delve deeper into the subject you will have to be able to distinguish, at least qualitatively, between self-assembly that relies on short-range and on long-range forces (long- and short-range is relative to molecular dimensions). To do that, a good place to start is to recognize that we already have considerably intuitive understanding of the Laws of Nature that determine phenomena we see on a daily basis.

Many physical laws have scale dependent consequences. As an example familiar to engineers, the (Newtonian) laws of motion for a fluid have several discrete ranges of applicability dependent on circumstances. Quite different mathematical solutions for fluids correspond to vast changes in the behavior of these fluids. One famous one is due to the 19th century English physicist, Osborne Reynolds. He observed that flow in a smooth pipe was gentle and sinuous with flow proportional to the pressure gradient Dp that caused the flow but, at a definite condition, where the so-called “Reynolds number” (representing the ratio of convected momentum to molecular momentum) exceeded ~ 2,100, the flow became chaotic and turbulent with flow proportional to the square of Dp.

In many physical systems we can assume that behavior is “scale” dependent with severe behavioral changes accompanying the different regimes. As a simple example consider a (fictitious) general solution to a problem described by:

![]()

in which “y” is some kind of phenomenon we wish to study that depends on some parameter such as “x”. We further suppose that A and B represent physical aspects of the same system. It should be clear that we could find some range of positive “x” in which either sub-phenomenon A or sub-phenomenon B predominates. For example we can always find a “x” large or small enough that:

In other words, by varying the range of the property “x” that we are looking at, we can investigate “y” when dominated by sub-phenomenon A or by sub-phenomenon B without one being effectively clouded by the other. The physical analogy is that of two blindfolded people trying to identify the properties of an elephant each by touching just one part of it. The tusks and the tail are both “elephant” (i.e., corresponding to our basic physical laws) but the local solutions (“A = elephant tusks” and “B = elephant tail” as correctly determined by our blindfolded investigators) are quite different properties.

We will eventually see that what we mean by “nanotechnology” will often fall between two ranges of scale: continuum (or classical) and atomic (or quantum). Obviously in this elementary course, we will not be delving deeply into the mathematics of these subjects, but we will try to make you aware that different phenomena are in operation and we are sometimes floating between two limiting scales (i.e., as if we have to deal with A & B in the above example simultaneously).

Essentially put, nanotech is about building and exploiting structures whose dimensions lie in the range of 1 –100 nm where one nanometer (nm)is about the size of 10 hydrogen atoms laid end-to-end). Drexler also uses the term, “Molecular Manufacturing” to describe the objectives of what is to be achieved in nanotechnology. He’s talking about structures that will 1) be useful, 2) be small, 3) be made by processes that exploit the laws of scaling that favor the chosen technology. However, be aware that some others in the same subject area hotly debate his views.

It is recommended you visit an interesting self-explanatory website entitled “Powers of 10”. This neat simulation will walk you through physical scales of length in jumps of one thousand starting with cosmological scales to the interior of the subatomic particles known as “quarks”. While this tour will wet your appetite, realize that it is simply a visualization of discrete phenomena; it shows the “what”, but not the “why” of how these objects get to appear as they are.

The first technical problem is that we span the scales of the classical and of the quantum limits. Where necessary both must be considered, but even before that mountain is climbed, we need to realize that we do not understand just how forces and energy scale as we reduce our vision to the chosen nanoscale. In order to make the subject more palatable, we will break it down into a number of subtopics; be aware this list is neither inclusive nor exclusive. In other words there are alternate approaches and the approaches presented below are not unique. Hopefully you will find it useful as you use the various embedded links.