The Quantum World

Quantum Mechanics

We are now in the realm of quantum mechanics, that aspect of mechanics that describes the “small”. The continuum laws or “classical” laws that describe the “everyday”, no longer apply as we reach into molecular dimensions. The gap is partially bridged by “statistical mechanics” of which “molecular dynamics” and the ideal gas model that we have just seen may be regarded as introductions. It’s outside of what is reasonable to expect of you in this stages of your careers to go into the mathematics of quantum mechanics, so the descriptions will be qualitative as we proceed and we will avoid the rigors of the subject.

Chemistry deals with the motion of electrons and is thus the province of quantum mechanics even though we observe its results by macroscopic quantities – which is why we use the mole as the preferred unit of size. When energy is released by burning something or by combining a couple of reactive chemicals, what has occurred at the quantum scale is that some electrons have changed locations from higher energy to lower energy states (sometimes in the other direction too). How this energy appears and what we do with it, is the realm of the inventive scientist and engineer, but it surely will appear according to the differences in energy between the final and initial states of those orbital electrons. Unfortunately, the subject is too difficult to pursue at this stage of your academic career, so we will be confined to a few comments and examples.

The expression ε = hn lies at the heart of quantum mechanics; it says that energy of a photon of light is “quantized” in packets at a specific frequency (expressed in cycles/s or hertz[1]) of n. Photons are emitted when electrons decay from a high-energy state (or orbit) to a lower one.

Chemically accessible electron orbits have energy levels that are measured in eV or fractions thereof. The takeaway is that in chemical reactions, the amount of energy absorbed or released when a chemical reaction occurs is of the order of a few eV or fractions thereof. For example, in natural gas combustion, if one molecule of methane is completely burned it produces one molecule of carbon dioxide and two molecules of steam + 9.73 eV of energy. Likewise the complete combustion of a molecule of H2 produces a molecule of H2O and about 2.6 eV. A major consequence of chemical energetics is that batteries and fuel cells (a type of continuously fueled battery), both of which depend on chemical reactions, are essentially low voltage devices; if you want more volts (i.e., potential energy from electrons) you have to put several battery cells in series.

There is one quantum mechanical result that is particularly worth quoting. It refers to the thermal motion of a quantum oscillator. This is a model for a solid crystal in which atoms in the material are vibrating. In this sense, it differs from the model of a gas where the individual molecules are free to roam; in a crystal, atoms are located about equilibrium positions and vibrate about those positions. The quantum mechanical model leads to a number of experimentally verifiable conclusions about the thermodynamic properties of such solids. The key result is:

![]()

This quantum mechanical formula relates the energy, εn of such an oscillator to Planck’s constant, h, and to its frequency n (expressed in hertz). Planck’s constant has the value 6.63 × 10-34 J·s. Typical molecular vibrational frequencies[2] are in the range of 1012 to 1014 hertz (cycles/second).

For the harmonic oscillator model, the energy levels vary in integral amounts of n = 0, 1, 2… Note: at n = 0, the oscillator still has a value, the so-called zero point energy of ½ hn. We can use the above formula to find the amplitude of the oscillation; in practical terms this is a measure of the fuzziness of locating a single atom on a surface, something that is important in engineering at the molecular scale.

To get there[3] we need first the averaged energy of a group of harmonic quantum oscillators. It’s obtained through their average energy,

![]() :

:

where

![]() is related to the mean square displacement of the oscillator, σ2, by

is related to the mean square displacement of the oscillator, σ2, by

![]() (ks is the bond strength between atoms, expressed in N/m, the model being the more the stretch, the larger the restoring force as in a spring described by Hooke’s Law). The displacement σ is what we are after since it tells you how much an atom oscillates about its equilibrium position.

(ks is the bond strength between atoms, expressed in N/m, the model being the more the stretch, the larger the restoring force as in a spring described by Hooke’s Law). The displacement σ is what we are after since it tells you how much an atom oscillates about its equilibrium position.

The exponential term, exp(-hn/kT), often shows up in quantum mechanics. It’s an exponential of a ratio of a particular kind of energy (in this case, vibrational) to thermal energy and is related to the fraction of particles in quantum state hn at a particular temperature. Obviously, as T increases, this fraction increases from zero until it’s 100% when the temperature is infinite.

The above exponential term has an analogue relating to the fraction of particles in a classical energy state,

E. The Boltzmann distribution is ![]() and it too relates particles and their energy. In fact it directly gives the fraction of molecules at a temperature

T that are in the energy state E. It can also be written in terms of the energy per particle ε =

E/NAv, so that the Boltzmann distribution can also be expressed as exp(-ε/kT).

and it too relates particles and their energy. In fact it directly gives the fraction of molecules at a temperature

T that are in the energy state E. It can also be written in terms of the energy per particle ε =

E/NAv, so that the Boltzmann distribution can also be expressed as exp(-ε/kT).

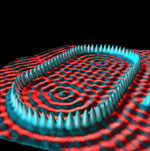

The inset figure is from Drexler[3]; it shows how a chemical bond (in this case between just two oscillating atoms) is affected by increasing temperature (the abscissa). The ordinate is proportional to the amplitude of the displacement of the atoms. The figure clearly shows both the classical limit (which is ultimately a Boltzmann distribution) and the quantum limit. What constitutes high or low temperature is also a function of the frequency of oscillation. Note too, how the magnitude of the oscillation, i.e., its amplitude, increases with temperature. Sometimes it is necessary to go to very low temperatures to get sharp images of small molecules or atoms. This has significance for the AFM.

Footnotes and References

[1]. You can convert into cycles/s into radians/second by multiplying by 2p.

[2]. A recent Nobel in chemistry went for the development of “femto-second spectroscopy” that is fast enough to reveal chemical bonding on-the-fly (“femto” = 10-15): http://www.nobel.se/chemistry/laureates/1999/press.html

[3]. K. Eric Drexler, Nanosystems, (John Wiley and Sons, NY, 1992), p. 92 et seq.