Nanotechnology

Thermal Scaling

The basic law of thermal conduction is named after its discoverer, Joseph Fourier. For Fourier’s law of (thermal) conduction, the mechanism of heat flow over macroscopic distances is diffusion. Diffusion is the spread of a property due to the fact it is more concentrated in one place than another. The material can lower its local energy by spreading it until it becomes uniform throughout the material.

Fourier’s Law states that the heat flow in a non-uniformly heated material is proportional to the temperature difference between two points and is inverse to the distance between those points. It applies extraordinarily well to macroscopic regions but it also leads to predictions that instantaneous thermal transmission speeds are effectively infinite over finite distances. In consequence Fourier’s Law should not be used at small scales at which more detailed mechanistic descriptions become necessary.

Written mathematically, Fourier’s Law also defines the thermal conductivity k of the material through which the heat is passing.

![]()

The heat flux q is the thermal energy rate per unit area perpendicular to the direction “x” of the heat flow. The linear gradient dT/dx is the mathematical representation of the statement of Fourier’s Law as given above.

The above description is mute as to the mechanisms of heat transfer under any of a number of differing circumstances. For example, local collisions between atoms or molecules will transfer energy if there is a temperature gradient. Simple gas theory leads to an expression relating thermal conductivity and the mean free path between collisions (see The Gas Laws):

![]()

in which ρ is the gas density,

![]() is the mean molecular

speed, λ is the mean free path and CV is the heat capacity of the gas (at constant volume). For solids, this is modified as follows:

is the mean molecular

speed, λ is the mean free path and CV is the heat capacity of the gas (at constant volume). For solids, this is modified as follows:

![]()

in which a is the speed of sound in the solid, λ is the mean phonon[1] free path (approximately meaning the amplitude of thermal vibrations) and C is the heat capacity (see below). If there is more than one kind of vibration present, λ is a corresponding average (usually an inverse sum as for electrical resistors in parallel).

Heat transfer mechanisms in materials may be due to the motion of electrons (i.e., in metals) or it may be the propagation of vibrations between adjacent atoms in nonmetals as described above. In non-metallic solids, local effects of phonon energy transfer can manifest differently from the overall heat conduction effects in that they propagate at the (finite and physically meaningful) speed of sound (usually of the order of a few thousands of meters per second in solids and varying from material to material as the square root of ‘stiffness’ divided by density). At macroscopic scales the combined effects of all of the mechanisms of thermal conduction will follow Fourier’s Law although at much slower diffusional speeds (see “thermal time constant” below) than the speed of sound due to the effects of multiple scattering impeding the flow of heat. In the intermediate distance scale the combined effects of local phonon transfer and simple heat diffusion can be coupled[2].

High quality diamond has a thermal conductivity of about 2 kW/m K and is the highest for any material. A diamond cube of 1 nm3 would thus have a predicted thermal conductance of 2 μW/K (meaning for a path length of 1 nm, two microwatts of heat flow rate would flow per 1°C temperature difference) provided Fourier’s Law holds over length scales of nm. However,as described above, conduction over short distances is dominated by non-diffusive phenomenon of phonon transfer, and not by Fourier’s Law.

A metal such as copper has an appreciable amount of heat transported by electrons that scatter off vibrating Cu atoms located in the copper crystal lattice. Its thermal conductivity is about 400 W/m K.

A thermal insulating material such as magnesia (MgO) has a thermal conductivity of about 30 W/m K and is obviously small compared to that of diamond or of copper. The principal reason for such small thermal conductivities is that multiple scattering of phonons occurs due to the presence of two or more kinds of atoms that renders imperfections in the vibrational pattern.

Heat capacity is a fundamental property relating to how much thermal energy can be stored (i.e., in the motion of electrons and phonons). Assuming that the thermodynamic property heat capacity is constant regardless of scaling, the heat content of a finite mass of material scales as its volume, or heat capacity is proportional to L3.

Diamond has a heat capacity of about 1.7 × 106 J/m3 K; for a 1 nm3 cube, its heat capacitance is thus 1.7 × 10-21 J/K. In eV terms this is 0.01 eV/K. At room temperature the thermal energy in this tiny piece of diamond totals 3 eV.

How long do thermal changes take to happen? It depends on a representative thermal time constant. For macro distances this can be derived from Fourier’s law. This shows it scales as (distance)2 × volumetric thermal capacity/thermal conductivity L2 ´ C/k or a thermal time constant that is proportional to L2. For our 1 nm3 diamond cube, this yields about 10-12 seconds - well within detection by today’s high quality instrumentation.

We can also see how quickly frictional heating occurs and produces local temperature distortions. Friction heating is proportional to friction power/thermal conductance or friction heating is proportional to L. Whereas friction will cause grave problems in macroscale systems, there is very little heating in nanosystems (according to this model).

| Property | Scaling Law | Property | Scaling Law |

| Thermal Conductance | L | Heat Capacity | L3 |

| Thermal Speed | L-3/2 | Thermal Time Constant | L2 |

| Friction Heating | L |

Table 1: Macroscopic Thermal Scaling Laws according to Drexler[3]

That’s really very good news if the model is correct to the nanoscale. However, some experimental work on friction using a AFM, shows a mechanical scribe scraping an atomically flat gold surface and transferring an layer of gold just a few atoms thick to the scribe. Apparently friction involves intimate molecular effects that were not anticipated from the previously known macroscopic laws describing frictional effects.

In the above discussion of frictional heating effects, a cautionary note was added with the conditional “if”. The fact is friction on the microscale bears little obvious relationship to what is observed on the nanoscale. Recent molecular modeling[4] suggest we should be cautious in accepting these macroscopic laws. Rieth’s[4] molecular dynamic calculations are a case in point.

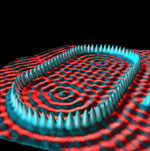

Figure 1 is adapted from reference 4. Here an aluminum pinwheel is made to rapidly rotate against a flat aluminum surface; at these scales, friction has a destructive effect, not necessarily apparent at the macroscale except in the generation of heat. The dissipative work that leads to macroscopic heating seems to be at the expense of bond breaking if we are to believe the M-D model illustrated in the figure.

Finally, the cautious student is warned also to test the limits of macroscopically-related scaling laws such as Table 1:

Example

What is the minimum physical scale distance that can be applied to thermal conduction in diamond and in marble (a form of CaCO3)?

| Material | k, W/m K | ρ, kg/m3 | C, J/kg K | a, m/s | λ, nm |

| Diamond | 2,000 | 3,500 | 560 | 12,000 | 250 |

| Marble | 3 | 2,700 | 860 | 5,500 | 0.7 |

In this table, the mean free phonon path has been calculated according to; it is clear that the continuum model (Fourier’s Law) breaks down at much larger distances for a high thermal conductivity solid such as diamond than for a low conductivity one such as marble. In other words the thermal scaling laws based on Fourier’s Law in Table 1 as suggested by Drexler[3] have limited utility unless caution is exercised in their application.

Footnotes and References

[3]. K.E. Drexler, “Nanosystems”, (Wiley Interscience,, John Wiley and Sons, 1992), p. 32 et seq.